Blogs

KDE Manifesto: On The Doorstep

Tags: KDE, Innovation Games, Agile, Craftsmanship, Manifesto, KDE Manifesto Genesis

This post is part of a series about the KDE Manifesto

As mentionned in my previous post, I have been on a very needed hiatus from public communication. It also means that I delayed indefinitely my series about the KDE Manifesto. If you don’t remember the first part, I advise you to read it again first. Now… Let’s resume the story telling.

We’ve previously seen why we needed a tool to answer this question of “What is a KDE project?“, in this part we’ll see how we tackled the task which led to the KDE Manifesto.

Because of all the events and the questions without answers related in the previous part, some people finally noticed some actions were needed and that we couldn’t ignore the symptoms any longer. At one point the discussion started in the KDE e.V. about trying to provide a definition of what is a “KDE project”. Then in the KDE e.V. was created a small team which had the mandate to create that definition. I had the honor to be part of that team, and the other members were Cornelius Schumacher, Eike Hein, Ivan Čukić, and Sebastian Sauer. We should really be grateful to the work they put in that task (I know I am).

We started with the right first step in my opinion: collecting feedback from the community and from different projects to see how they perceive themselves and the community. But doing it this way had a downside, we ended up with way too much data, and got completely overwhelmed. That was clearly not easy, and everyone being busy as usual at some point the data got ignored, collecting dust in a dark corner of our hard drives. The team became completely dormant and no communication was going on anymore.

Until… one night… I don’t really know why, I picked up everything and tried to map it on paper. I extracted criterias and definitions out of the pieces of text we received. After all, I used to do Knowledge Engineering, that couldn’t be an impossible task! That’s when I noticed why we felt overwhelmed and silently gave up on the task at hand. If you took all the criterias and considered them equals (which was our mindset all along), you could end up only with a tautological situation: “A KDE project is a project considering itself part of KDE or started by a known KDE contributor”. Not a terribly useful outcome, but at least I then knew how to move forward.

I asked the membership of the KDE e.V. to change our mandate in order to move away from trying to define what a KDE Project is and instead determine which characteristics we want KDE Projects to share. It sounds similar but makes a huge difference, you’re not working on a closed check list anymore. It made for a much more open space, and not all feedback could be treated equal anymore, there definitely was noise in there.

Once that change of scope got accepted, I summoned the original team again to set up a meeting at Akademy 2012 to work together on the data again. With the given mandate, it was likely not possible to nail it down in finite time remotely. Since not everyone could make it to Akademy, we had to reshuffle the team a bit to make the meeting happen.

And so the meeting finally happened at Akademy, after the KDE e.V. general assembly in presence of Alex Fiestas, Albert Astals Cid, Carl Symons, Cornelius Schumacher, Mirko Boehm, Pradeepto Bhattacharya and myself. We were looking at a very long and intense brainstorming session to go through all the notes which were collected the past months and try to make sense out of them… We all know how this kind of brainstorming sessions can quickly go out of control and be in the end fruitless. That’s why I came with an experiment to propose.

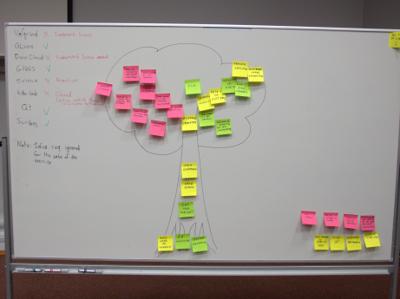

Instead of debating the outcome, I proposed a very light process, in the form of a tuned “Prune the Product Tree” game. This game is part of a set named “Innovation Games” which are good for market studies, or emergence of answers to very broad questions like the one we were tackling.

The basic idea is that we went through all the feedback we got, and for each piece of information found, we tried to determine where on the tree it would fit:

- On the floor if that was irrelevant, or mentionned as something we should avoid as a criterion in the future;

- On the roots if that was something supporting the community, something the community couldn’t function without;

- On the trunk if that was something central to the community definition;

- On the canope for anything less central, and derived from the rest, further away from the trunk as it was more refined by-product, in other words consequences from what was on the roots and the trunk.

And so, while playing that game (it’s a serious game, but a game nonetheless so it has to be played!) we obtained the following tree:

That’s when it struck me… We’re not really creating a definition, we’re creating a manifesto. On the roots and the trunk it was clearly on the values level, while on the canope you could see practical consequences of those values. I suggested the rest of the team to work on a document which would follow this form: the real manifesto talking only about the high level values, and then extra parts for the practical consequences of those values. This proposition was accepted by the whole team.

Before parting, we also decided to sanity check our result and get an idea of its impact on existing projects. We took a few sample projects and examined them through the tree we produced. Obviously sample projects which were already KDE projects would have to fit, and for sample projects which were not KDE projects we would need to easily identify the blockers for them to join. Reassured by this last check, we parted ways and the editing work started.

I ended up carrying that editing work. I took inspiration in the Agile Manifesto and the Software Craftsmanship Manifesto which went through this kind of exercise before us (“stand on the shoulders of giants” they say). While creating the different drafts, I proposed them to more and more different people, collecting feedback and amending as I go. That led us to the release of the KDE Manifesto in its current form. It is definitely not a document set in stone, I keep collecting feedback and I plan to push updates to the manifesto in the future. I expect the main page to be rather stable, but we’ll probably see the rest of it change with time. It seems I turned into the de facto curator for the KDE Manifesto, it’s something I try to approach humbly as to not betray the spirit of KDE.

And that concludes this genesis of the KDE Manifesto… it is definitely not the end of the process I mentionned in my previous post. We’re really on the doorstep, this document is more or less our late constitution, it’s up to the community to choose the path from here. I’m pretty sure it will be full of adventures for the years to come… That’s why, even though I generally avoid to do that, in the last part I will try a small exercise in forecasting and see which changes it might bring to the community.